Andrea Bruciati

"Something really worth remembering is that the last works of certain artists and the paintings they left unfinished (…) are more admired as such than if they had been completed: in them, you can observe the phantom of the missing part and thus perceive the artist's very line of thought. And the regret for the hand that is no longer – that left us when it was busier as never before – beguiles and feeds the public's admiration."

Pliny, Historia Naturalis, XXXV, 145.

Â

In February 1968, Art International published an extensive essay by Lucy Lippard and John Chandler entitled "The Dematerialization of Art." The artist's interest in the gradual disappearance of the object in favor of process and ephemeral materials is the overarching thematic of the text. Such a progressive absence of physicality demonstrates the artist's unexpected loss of interest in the physical evolution of the work, evolving instead into the artist's desire to change material into energy and concept.

The work is emptied and deprived of its dimensions 'of the senses'; it becomes a non-retinal structure that transforms the idea into an intellectual tension. An attention to the impalpable and the conceptual necessarily highlights diagrams, sketches, schematics – the gaseous state of the elements of the work's creation – so that the object becomes, in the words of Emilio Prini, something predisposed to 'thorough disappearance'. The resulting outcomes avoid unambiguousness and clarity, regularity and stability, in favor of open, changeable, contingent situations. The prevailing attitude aims at overcoming the object as an aesthetic final product complete in and of itself, while the artist's involvement focuses on process and siting. As a result, the importance of realizing a priori concepts – such as composition and material form – wanes: the agency and intentionality of the artist and his or her materials is subjugated to the free manipulation and experimentation of matter and of its possibilities for mutability and contingency (e.g., changing effects of light, use of perishable or ephemeral materials, or physical consumption by the artist or audience).

The pre-eminence of the creative process over the product leads to situations where any superficially perceived balance is revealed to be genuinely unstable, identifying the work as a possible 'episode' within a potentially unlimited process-driven course of events. Indeterminateness is a common denominator of such work. Artistic experience, in fact, appears as an uninterrupted and heterogeneous experiment in the dissociation of sense perception and cognitive reading. In the work of a few highly accomplised artists, such as Robert Barry, Hans Haacke, Douglas Huebler, Robert Morris, and Bruce Nauman, the 'process' component occurs through the instability of perceptual experience, driving things to an unpredictable breaking point, by becoming something other than themselves. Making the sculptural form relative, changed into a different thing, the loss of unambiguousness, on the material plane as well as on the semantic one, allows the work to manifest itself as an intervention. Regard for change, for the passage of states of being, represents a renewed source for inquiry, adhering as it does to the instability of categories. The metamorphosed condition takes on pre-eminent importance, not the least as a disruptive factor in the conceptual attitude of artistic achievement. Suspension and dislocation, the choice of non-localized activity, the choice to modify appearance into a phantom-form, however, permits an absence to be present over time. Two artists currently exploring this avenue of investigation include Jordan Wolfson (New York, b. 1980) and Nicola Gobbetto (Milan, b. 1980).

In Dreaming of the Dream of the Dream (2004), Wolfson selected over a hundred clips of animated cartoons depicting water – surging seas, bubbling rivers, crushing waterfalls, rainstorms and deep oceans – and spliced them together to make a 16 mm film. The only sound – the soundtrack to the compilation – is made by the noise of the projector. The sequence passes from sunrise to sunset, and suggests a lifeless, primeval world. The resulting product is a work that uses an amateurish language, lending the work an 'old fashioned' feel, heightened by the fact that the film appears to have been consciously and materially damaged. But in fact we are watching a unique film, as the artist has stipulated it cannot be duplicated, so, over time, the celluloid will wear and fade, slowly self-destructing. In Star Field (2004), a 16mm film loop, we have a similar situation:

a PC screen saver transferred onto 16-mm film and played in a continuous loop until the film's image disappears, consumed by its own presentation.

Wolfson's speculation could be thought of as a Romantic-Conceptual approach; the stakes are high because it is the constitution of the work of art itself that is called into question. By exploring the silent terrain between fiction and reality, the artist in fact seeks an alternative, authentic direction, preserved from the visual saturation of our usual, everyday media overload.

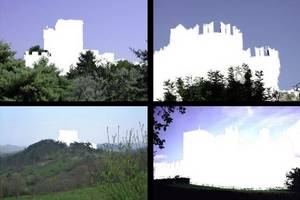

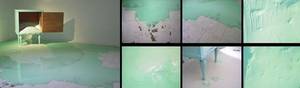

Nicola Gobbetto has followed a different approach in his own research. He places the ambiguity of sensory perception – always aimed at visual estrangement – in the change of state, in the annulment of the initial conditions of matter. The consumption and perishability of the icon – substantiated through sickly-sweet materials linked to our childish, inner dimension – are at the core of his reflections. The artist, in fact, investigates the instability of images by continually approaching the dreamlike. Accordingly, in Phantom Manor (2004), a castle attains a ghostly state and disappears from our sight into a white silhouette, while in Ice Dream (2004) the attempted creation of a solid ice-cream sculpture witnesses the nth defeat of our dreams, by visualizing the attempt to keep, to maintain something that, due to its nature, is subject to change, to alteration. In Sweet as Sugar (2005), which features twelve shots portraying a pair of small white canaries, what we see documented is the exhaustion, the wearing out of the work, which, in its "death" becomes food for the surviving, cannibalizing twin. Gobbetto's research continually oscillates between contrivances and fiction, as demonstrated by the affecting optical decoration on the floor in Snow (2006), an interior space consisting of powdered sugar circles that begin to dissipate as one walks around and through the installation.

Completion for Gobbetto, as a matter of fact, becomes both the corrupting action and the main cause of the work's (self)destruction, conceived as it is from the very beginning by the artist so that the work's formal purity is upset, as if the perfection of beauty were no longer a peculiar imperative in this world of ours.